2012 IN REVIEW

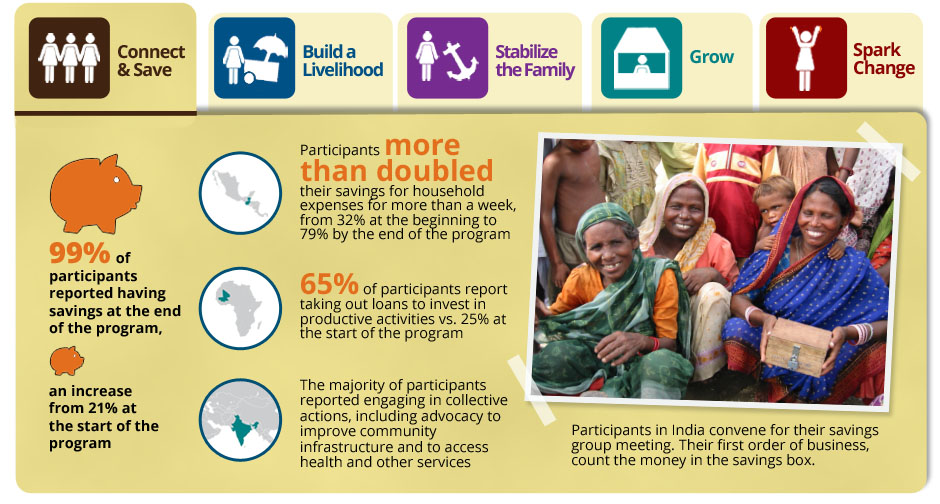

When women in India, Mali and Guatemala come together in a savings group circle, they build savings, grow their businesses, gain confidence and work in solidarity with one another. Together, in their circles, these women begin to reap the rewards of hard work. Soon, they are improving the lives of their families by giving birth to their newborns in hospitals, sending their children to school for the first time and ensuring their families have enough food to eat.

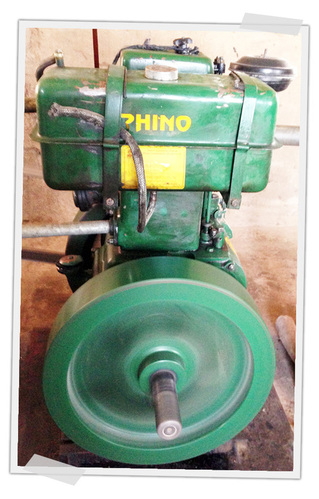

The Multifunction Platform of Pinou, Burkina FasoIn a Burkinabé village, there exists a large green machine connected to a belt with a blue cone on top. Women of the Rel Wendé savings group bought it over a year ago with their collective savings to help them more efficiently mill the grain their businesses produce annually.

It has become a symbol of pride for all the residents of Pinou. So much so that when Trickle Up staff visited in late 2012, they were eager to show us just how important the multifunction platform is to their lives.  Click to Read More Click to Read More |

You know you’ve reached Trickle Up country when the road has ended and you have to walk at least a quarter mile to reach the village. The village of Pinou is a two-hour drive west of Ougadougou, the capital of Burkina Faso, and we were definitely in Trickle Up country. Pinou is one of the poorest villages in one of the poorest nations in the world. Our journey began on paved highway, switched to a well-traveled dirt road, and then, beyond the small town of Koudougou, there was only a bumpy, rutted 2 mile path through the brush. We didn’t enter Pinou on foot, but probably should have.

When we arrived at Pinou, we were greeted by 25 women who are Trickle Up participants, all singing, clapping, and dancing in traditional African welcome. Three male drummers, with round traditional drums, known as Bendrés, kept the beat. Surrounding the women was another large group of women who joined in the song, punctuating it with an occasional high-pitched “lo, lo lo.” Their song called out, “We welcome you, we’re happy to welcome you. Come in, have a drink of water, make yourself comfortable, and, when you’re done drinking, we’ll catch up.” Continuing their song and dance, the women led us to the central clearing in their village.

When we arrived at Pinou, we were greeted by 25 women who are Trickle Up participants, all singing, clapping, and dancing in traditional African welcome. Three male drummers, with round traditional drums, known as Bendrés, kept the beat. Surrounding the women was another large group of women who joined in the song, punctuating it with an occasional high-pitched “lo, lo lo.” Their song called out, “We welcome you, we’re happy to welcome you. Come in, have a drink of water, make yourself comfortable, and, when you’re done drinking, we’ll catch up.” Continuing their song and dance, the women led us to the central clearing in their village.

|

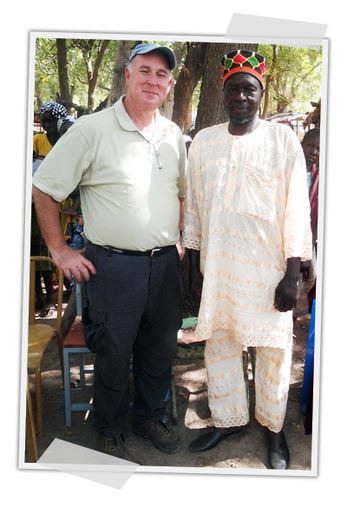

At least 300 more people were waiting there, including men, children, and the village chief. We were invited to sit in chairs beneath an enormous boabob tree and offered a cold drink. Behind us we heard an army of small feet shuffling in the leaves, and we turned around to see all the students pouring out of the local village school to join the crowd. While we are accustomed to generous greetings of song and dance when we arrive in an African village, this was extraordinary. The entire village had come to welcome us and thank us for what Trickle Up had done to change their lives.

|

The Trickle Up group had named itself Rel Wendé, or “Leaning on God.” Formed two years earlier, it consisted of 25 women who were among the poorest in the village. With business training provided by our local partner AIDAS and Trickle Up seed capital grants of about $125, each woman had begun a small enterprise to add to her family’s income and assets. Several made and sold soumbla, a flavorful African bouillon, and spices made from various grains. One woman fried bean cakes called samsa to sell, another sold peanuts, and two had started small restaurants. Several women brewed a local beer called dolo, and others grew millet sprouts that are used to make dolo.

|

In addition to providing business training and seed capital grants, Trickle Up helped the women organize a savings group. They meet every Friday, collect 500 West African francs (about $1) for savings, and contribute an additional 100 francs to a group social fund that is used to help members struggling with illness or another emergency. At their weekly meetings, after starting with a song and collection of the weekly savings contribution, which they keep in a small locked wooden box, the women talk about what is going on in their businesses. They give one another advice and offer encouragement to those who might be struggling. One woman told us how her business selling soumbala wasn’t producing enough profit, and the group recommended that she start an additional business buying grains at wholesale at the very start of their market day and then waiting until the end of the market, when other grain sellers had sold out, to sell hers at retail to take advantage of last-minute shoppers. American investors would recognize that as day-trading or arbitrage.

We asked what happened if someone in the group was facing hard times and couldn’t afford her weekly contribution to the savings fund. “We have lots of solidarity in the group,” Aminita, the group president, explained to us. “If someone is sick, a few of us will go to her house to check on her, and we’ll each save a bit extra to provide her weekly contribution. We all know that tomorrow it could be any one of us in her position.” machine with a large cone on the top. It was the largest building in the village, except for the school. In addition to milling the village farmer’s grain into flour, it was used to husk the grains and provide power to charge batteries. In the future, with additional components, it also could generate electricity for the entire village. The women of Rel Wendé—poor women who had never been to school and had little status in their community—told us how they were responsible for building the Multifunction Platform. Someone from the local government had heard about this group of 25 women who met weekly to save money and lend to one another, as well as providing mutual support. He informed them of a government program that would help fund a mill for the village, so long as it would save women work (they would spend untold hours grinding their grain by hand with traditional methods) and build the capacity of a local women’s group. |

In its two years, the group had saved a total of 1.53 million francs, or about $3,000. Members are able to take small loans from the common treasury, so most of the funds are out in circulation rather than stored in the savings box. The group’s social fund currently had $200. This is a typical Trickle Up story. What comes next is not. When we first entered Pinou, we had noticed a brick building with a sign above the door announcing that it was the “Plate-Form Multifonctionnelle de Pinou,” or Multifunction Platform of Pinou. Inside was a large green engine connected by a wide belt to a milling |

To qualify for the mill program, the women had to formally register their group with the government. They also had to put up 300,000 West African francs (about $600) in order to leverage a government grant of 5 million francs ($10,000). Since 300,000 francs was all they had in their savings fund, they were unsure if they should risk it all and so they went to AIDAS, Trickle Up’s local partner agency, for advice. They also consulted with the village chief, who encouraged them to do it and offered to provide 1,000 bricks to help construct the mill building. The women each contributed 25 bricks of their own and persuaded others in the village to contribute lumber for the building and cement for the floor.

The Multifunction Platform opened for business in May 2011. Women from the Trickle Up group take turns operating the mill. They don brown work jackets and hairnets, with one woman monitoring the main engine and another the milling component, where villagers pour grain into the funnel on the top and then collect the milled grain in buckets or burlap bags at the bottom. Profits from the mill go back to the Rel Wendé savings-and-loan fund, which is now able to also make loans to another group of women, who, on their own, are establishing their own savings group.

The Multifunction Platform opened for business in May 2011. Women from the Trickle Up group take turns operating the mill. They don brown work jackets and hairnets, with one woman monitoring the main engine and another the milling component, where villagers pour grain into the funnel on the top and then collect the milled grain in buckets or burlap bags at the bottom. Profits from the mill go back to the Rel Wendé savings-and-loan fund, which is now able to also make loans to another group of women, who, on their own, are establishing their own savings group.

|

As important as the economic benefits from the mill facility are, it also has given the community a much-needed resource and boosted the social standing and prestige of this group of women—once among the poorest and least influential in the village. “Now other women see us as a reference,” Aminita said proudly. “They want to resemble us.” Other women in the village, inspired to start their own savings group, have come to the Trickle Up women to ask for advice.

After hearing the story of the women of Rel Wendé and the Multifunction Platform, we understood why the entire village—including the chief—turned out to greet us today and honor this group of resourceful and determined women whom Trickle Up is helping to better their lives and contribute to the advancement of their community. |

Rudhe Khersil and her Savings Circle, IndiaRudhe Khersil was pregnant when she joined her savings group. As the months passed, the women in her group became concerned about her health and the conditions she would be exposed to if she gave birth in the village.

Watch the video to see what happens.... |

|

Sitting in a Circle, Weaving the Social Fabric of Guatemala

When the women of Las Azucenas came together five years ago to start their savings circle and join the Trickle Up program, they never imagined that their collective actions over the years would help mend the torn social fabric of Guatemala. Learn how their weaving has helped them, their community and the country as a whole.  Click to Read More Click to Read More |

Guatemala is a beautiful country. Its many mountains and hills take you through windy roads to beautiful vistas reminiscent of fantasy novels, while 19 different microclimates, including hot deserts, steamy tropical forests, and wet rainforests, ensure ever-changing scenery. So, it was a wonder when my colleague on this recent trip to Guatemala described the country as one where the “social fabric” was “ripped to shreds.”

There is certainly some truth behind this statement. Guatemala is a country with a dark past: thirty-six years of civil war ending relatively recently in 1996. This was a drawn-out war during the height of the leftist, communist scare of the Americas. The government of Guatemala ran a terror campaign against poor, rural communities, mainly indigenous peoples, whom they believed were supporting the rebel groups. Some attribute the military’s actions as genocide. Indeed, the destruction of entire communities and villages resulted in some 200,000 killed and 40,000 to 50,000 missing.

To add further complexity to this tragedy, these affected communities are also home to some of the poorest and most vulnerable people of the country—those who live in the conditions of ultrapoverty. The ultrapoor, a subset of the extreme poor—those who live on $1.25 a day and less—are characterized by chronic food insecurity and poor health, insufficient and irregular income, minimal productive assets with high vulnerability to shocks, and the need to prioritize consumption over investment. They have been historically excluded by their own government and NGO programs. The ultrapoor tend to be disproportionately women, indigenous, rural, and people with disabilities.

In Guatemala’s case, the socioeconomic inequalities created as a result of marginalization and violence against the rural, indigenous population has left 76 percent of indigenous households, over 4.1 million people, living below the $1.25 a day poverty line. Even more, indigenous women have a literacy rate of only 38 percent, compared with 76 percent for nonindigenous women and 43 percent for indigenous men.

So, it was fascinating to me to see it was those who live in these dire conditions as the ones who were doing so much to rebuild—or, more specifically, re-weave—their communities.

To add further complexity to this tragedy, these affected communities are also home to some of the poorest and most vulnerable people of the country—those who live in the conditions of ultrapoverty. The ultrapoor, a subset of the extreme poor—those who live on $1.25 a day and less—are characterized by chronic food insecurity and poor health, insufficient and irregular income, minimal productive assets with high vulnerability to shocks, and the need to prioritize consumption over investment. They have been historically excluded by their own government and NGO programs. The ultrapoor tend to be disproportionately women, indigenous, rural, and people with disabilities.

In Guatemala’s case, the socioeconomic inequalities created as a result of marginalization and violence against the rural, indigenous population has left 76 percent of indigenous households, over 4.1 million people, living below the $1.25 a day poverty line. Even more, indigenous women have a literacy rate of only 38 percent, compared with 76 percent for nonindigenous women and 43 percent for indigenous men.

So, it was fascinating to me to see it was those who live in these dire conditions as the ones who were doing so much to rebuild—or, more specifically, re-weave—their communities.

|

Las Azucenas savings group in the city of Tamahu does all of this, and so much more. This group was started more than four years ago by 19 Trickle Up participants. It has since expanded to 35, and 13 of the original participants remain in the group. Of the 35 members, it has accepted its first two men into the group. At the end of its previous fourth cycle, Las Azucenas had a total savings of 13,500 quetzales (approximately $1,800), and 1,300 quetzales (approximately $175) in a social fund that is used for non-business expenses agreed upon by the group. To me, Las Azucenas represents the work required to “weave” together Guatemala’s “torn social fabric.” When the women came together five years ago, they were working in a society that was (and continues to be) mending its wounds from a civil war that ended more than a dozen years ago. They wanted to end the marginalization they have faced in their country and community by building sustainable livelihoods through savings and solidarity. |

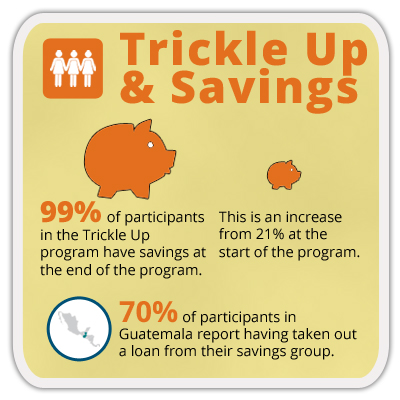

Nowhere was this better witnessed than with the women I met sitting in their savings group circle, Las Azucenas. Trickle Up’s program focuses on providing business training and a grant to start meaningful livelihoods for people living in the conditions of ultrapoverty. However, the sustainability of these livelihoods comes from the savings groups the women join at the start of the program. It is important to recognize that, for most people living in these conditions of ultrapoverty, there exist no insurance programs to fall back on in the event of an emergency. If disaster strikes, families are often forced to sell what few assets they have and take out the only loans they have access to, those with high interest rates. All of which lead them further into poverty. By joining savings groups, women are able to protect their families by coming together to save so as to buffer against such shocks while also being able to access credit to grow their businesses.

|

Now, they are a tight-knit group that has developed a rigorous set of rules to work together and continue to move out of poverty. For example, potential new members are investigated and not admitted if they are found to have bad credit or outstanding debt. Even then, the group does not extend credit to new members until they have been members in good standing for at least six months. Furthermore, they support one another and their communities, last year using their social fund to support a neighboring village that was affected in a landslide. And finally, they have positioned themselves as an important part of their local community: Meeting times and other information about the group are broadcast over local radio, they have been given access to the main municipal building in the city of Tamahu to hold their meetings, and the assistant mayor and several other members of local government were present when we visited.

|

What’s more, many of them are actual weavers themselves! In fact, nearly 45 percent of Trickle Up participants in Guatemala choose weaving as a livelihood activity, since back-strap weaving is passed down from generation to generation among the indigenous women of Guatemala. There is always a decent market for it with the country’s growing tourism sector. Many of the women had actually brought their products to show to us. In fact, I ended up buying a few of the brilliantly colored weaves and turned one into a pillow. Every time I look at it, I’m reminded that I not only own a part of Guatemala’s heritage, but also a piece of its future. That is, the hard work that women like Las Azucenas do in re-weaving the social fabric of their country whole once again.

|